In the post-Tagore

era, Jibanananda Das was much discussed, and his new kind of poetry written in the

tradition of Eurocentric modernism engrossed the attention of a good number of critics.

Even Tagore called him chitrorupmoy (Basu

2004). Several books and articles have been written regarding western influences

on him, his use of image and metaphor, his sense of pathos and agony of modern man

and so on. He was the pioneer of modernism in Bangla poetry. The American scholar,

Clinton Booth Seely has regarded him as Bengali’s most cherished poet since Rabindranath

(Basu 2004). A researcher, Audity Falguni wrote in her article, “Jibonananda Das:

Poet of Autumnul dew” about Das’s contribution in internalizing the changed worldview

and expressing the new paradigm with suitable poetic language in Bangla poetry.

In another article, “Surrealism: From French to Bangla literature” published in

the Daily Star, Abid Anwar claimed that

in Bangla poetry, Jibananda Das used surrealistic imagery for the first time. Arunima

Ray in her article, “Understanding Jibananda’s different Poetic sensibility” discussed

Das’s adopting different Eurocentric modernist traditions and presenting them in

different dimensions.

Dipti Tripathi, a

renowned critic of West Bengal, has considered Jibananada to be the first surrealist

and impressionist. She has taken references from different poems to demonstrate

his surrealistic approach. She has also discussed that Jibanananda, being influenced

by Western literary movement, wrote surrealist poems as well as expressionist and

impressionist poems. Besides, Saikat Habib has edited a book titled Banalata Sen: Shat Bochorer Path that contains

a good number of essays written by some prominent writers like Fokhrul Alam, Shamsur

Rahman, Abu Taher Majumdar, Abdul mannan Sayeed, Buddadev Basu, Klington Booth Seely,

Humayan Ajad, Shunil Gongo Paddhay and others. All these great writers shed light

on the popularity of the poem, aesthetic value and higher poetic truth and beauty

and western influence on this poem. Jibananada Das belonged to the group of poets

who successfully created post-Rabindranath era shaking off Tagore’s poetic tradition

replaced by western modernism.

Jibananada integrates

Bangla poetry with the Euro-centric modernist movement of the twentieth century.

His poetry explores the gradually sprouting 20th-century modern mind, sensitive

and reactive, full of anxiety and tension. He is highly individualistic and a modernist

having idiosyncrasies far-fetched comparisons, abundant use of apparently incoherent

imagery, sense of fragmentation and wizardry of images. However, his work is shot

through with the celebration of natural beauty. Instead of reflecting a shift away

from Tagore’s idealism and approaching urban life like other modernists, Jibanananda

skillfully applies modern approaches like surrealism or impressionism, with natural

beauty and phenomenon. With his self-styled lyricism and imagery, he creates an

appealing and unfamiliar world as we see in his well-read poem Banalata Sen where a sense of time and history

is mingled with nature and beauty.

In the early 20th

century a new poetic movement called imagist movement led by Ezra Pound, emerged

with the publication of Literary Essays of Ezra Pound. Nature and characteristics

of this new movements were given in the preface “A Retrospect”. He for the first

time used and defined the term Imagist—an intellectual and emotional complex in

an instant of time” (qtd in Mitro 1986). This abrupt presentation of merging intellect

and emotion applies poetic beauty and pleasure. Influenced by this movement, Jibanananda

and other post-Tagorian poets skillfully employed juxtaposition, comparison and

other aspects of this movement in Bangla language.

In Banalata Sen we encounter a tired soul of a journeying poet looking for

tranquillity and breathing space. At once he comes across Banalata Sen, and merges her beauty with classical antiquity and on

the other hand, makes her illustrative of Bengal, Bengal’s nature, its deep solace

and shelter as he says:

For a thousand years I have walked the ways of the world,

From Sinhala’s Sea to Malaya’s in night’s darkness,

Far did I roam. In Vimbisar and Ashok’s ash-grey world

Was I present; Farther off, in distant Vidarba city’s darkness,

I, a tired soul, around me, life’s turbulent, foaming ocean,

Finally, found some bliss with Natore’s Banalata Sen.

(Alam 2004)

The writer, as we

find in the lyric, has gone far and wide, yet nothing could vanish his exhaustion.

It is just when he encounters Banalata Sen,

he feels peace. Jibanananda gives open chain to his creative energy represented

by his movements to antiquated and remote spots of incredible excellence and fascination.

After his mission, he finds only life’s frothy

ocean (Das 2014). This perception ultimately brings him back to Bengal, especially,

to Banalata Sen; then the poet makes it

specific and real, adding the name of Natore. Soon after this rootedness that instils

into him the memories of Bengal is replaced with otherworldly feelings and striking

sensation. When he portrays Banalata Sen, he draws comparison utilizing pictures

which offer an overwhelming impression of the individual. As the speaker encounters

her, she says, Where have you been so long?

And raised her bird’s-nest-like eyes— Banalata Sen from Natore (Das 2014). This image comes out brilliant and suggestive.

Jibananada’s drawing parallel of Banalata

Sen’s bird’s-nest-eye image is a mingling

of imagination and intellectualism. It has opened a gateway to the surrealistic

domain where an exotic touch to the commonplace things makes us perceive the unexpectedness

and weirdness in the ordinary.

In Jibanananda’s

Banalata Sen the influence of surrealism

and impressionism is revealed very clearly at the very beginning of the poem. Surrealism

is vigorous spontaneity with which thoughts are free from all restrictions, such

as preoccupation with rationality. It reaches the centre point of the mind where

past and present, death and life, real and imaginary—all opposing forces drop their

antipathy. In Banalata Sen the Poet’s

hyperbolic expression of roaming the world for thousands of years or entering ancient

India during the reign of Ashoka releases the readers’ mind from rationality. Being

influenced by Freud, the poet suspends the conscious self that makes known all abstract

aspirations and sense of wonder. The poet combines several techniques depicting

various aspects of life and civilizations. He steps forward to the end of life after

passing over the history and heritage of thousands of years. During his journey,

he encounters mystery, exhaustion, relief and fatigue. The poet as we see in the

poem has travelled ancient and remote places of great splendour and magnificence.

However, with the passage of time, he perceives the entrenched emptiness that is

filled with an overwhelming and undiscovered truth. After passing various prairies,

the enthusiasm of ocean and mountain, beauty and truth of the heritage, he has got

a sigh of relief in Banalata. The poet abolishes all the barriers between consciousness

and the subconscious, inner self and outer reality.

After passing Maloyan

ocean, Oshoka, the ancient Indian king and Bimbisers as well as the ancient city

Bidhharva, all of a sudden, the poet becomes surrealist; he combined the beauty

of thick black hair of Banalata incoherently with the images from old and lost civilization,

and this bizarre and far-fetched comparison creates surrealistic vibes. Association

of the beauty of hair and face with Vidisha

city’s night and art work of sravasti

surpasses everyday commonplace reality and usual timeframe. Exhaustion and dreamlike

atmosphere are inter-related. Sense of nuisance and inertia bring about a tendency

to escape in an ideal land. On the one hand, comparing himself with ship-wrecked mariner who has lost of land,

the poet emphasizes his weariness, and on the other, he creates a sense of wonder

and beauty of a dark and ancient civilization.

Here the languid

and trancelike situation is created after colossal exhaustion and fatigue as the

speaker says the sea of life is lathered.

Worn-out with the madding crowd he is now a weary

spirit that finds transitory peace in Banalata

Sen. He creates a surrealistic tone with the sense of wonder and beauty of dark

ancient civilization. This beauty is enhanced with the natural image of green grass in Cinnamon Island. Then there

is a turn from surrealistic world to reality as a conversational note appears That way I saw her in darkness, said she: Where’ve

you been? (Das 2014)

Though all these

happened in reverie, the poem seems at the point indistinct as the poet adds a title

to Banalata along with the name of her birthplace, Natore. Ambiguity occurs, as

he adds the title and the name of the place, as well as he creates a dreamy land

of natural beauty with some sprawling images. Combining bizarre image with a conversational

tone, he mystifies the reader. At this point Reader’s mind keeps swinging and wavering

for the quest of unfathomable Banalata.

All birds home- rivers too, life’s mart close again;

What remains is darkness and facing me – Banalata Sen!

(Alam 2004)

There is a hidden

conflict amongst life and death, movement and immobility, activity and inaction,

real and surreal. The artist says that it has been a thousand of years since he

has begun trekking the Earth. He depicts it as a long excursion in night’s obscurity

from Cylon’s water to the Malayan oceans. However, the reason for his roaming around

the world is not clearly stated in the poem. But the image sea of life is suggestive of a worldly affair. But this worldly affair

is given an extra flavour of exaggeration. From this land spread, he goes ahead

to the extent of time alluding to his meandering, he has navigated the blurring

universe of Vimbisara and Asoka and then to the forgotten city of Vidharbha. Here

the reference to the lost ancient city and image of darkness and grey colour take

us to the surreal domain. The image of darkness recurs when he compares her hair

with long-lost Vidisha and when he sees her in Cinnamon Island. In the last stanza,

darkness is approaching and at the end of the day evening crawls like the sound

of dew, and all colours take leave from the world except for the glimmer of the

hovering fireflies. The recurrent image of darkness is congruous with the line When all the colours of world fade, those Manuscripts/Prepare

for the stories. Manuscript of life prepares the whole story, and then, the

transaction of worldly affair terminates. The poem that starts with the poet’s continuous

roaming ends with a note of stillness. Though the last part of the poem is suggestive

of the end of life, the poet implies nothing beyond death. But a death like stillness

is prevailing when all activities with the impending tranquil evening come to an

end, and all the colours are wiped out due to the impending darkness. This is a

world apart that reminds us of Robert Frost’s yearning for last sleep stated in

his poem “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”. Frost expresses his desire for

sleep after finishing the worldly affairs whereas Jibananada has already reached

a dreamlike respite completing all the transactions of life.

Darkness and weariness

are prevailing in the last stanza of the poem where the poet makes an incoherent

and surrealist world that is evocative of the end of life. However, beneath the

apparent incoherence and inconsistency, meaning lies. His sense of fatigue and craving

for rest turn to inebriated obsession. Now he seems to be under the spell of delirium,

at what time he feels she is approaching silently like dew-drop falling. It is a

motionless world where remain only prevailing darkness, appalling silence and sitting

passionately face to face.

In his poem, the

colourful natural beauty connecting subtle perceptions creates a thread of thought

that is given fullest expression. Skillfully applying the words and combination

of various colours of natural beauty creates artistic emotion with sensory perception.

Impressionism poles apart from realism and is based on intellect and common emotion.

Impressionism, however, in its sensuousness keeps itself aloof from reality creating

a new atmosphere with the mental impression and subtle perception about the beauty

of the material. To the impressionists, the word twilight is very significant. This

transitional period between day and night when mingling of light and darkness prevails,

the poet paints a domain of his own where realism is suspended, and the mental impression

is invigorated with all powerful perceptions displaying darkness and colour image:

At the end of the day, with soft sound of dew,

Night falls; the kite wipes the sun’s smell from its wings;

The world’s colour fade; fireflies light up the world a new;

(Alam 2004)

With the darkness

and colour image like grey and green, the poet creates a visual description of his

imaginary domain. Darkness throughout the poem evokes subjective and sensory impression

rather than objective reality. Darkness prompting and mystifying the reader’s imagination,

calls for individual and subjective interpretation. The poet has roamed much the dark seas of Malaya. Then he has been

in darkness of Vidarbha. He remembers her hair dark as night at Vidisha.

Even the poet sees her in the midst of “Cinnamon island” that is also dark. Eventually,

only darkness remains, and Banalata sen appears visible through the darkness. The

poet takes the reference of light of fireflies

that only deepens the darkness. The poet gives impressionistic touch by aesthetic

experience comprising some visual beauty inherent in things. Subjectivity is the

way the mind looks at the combination of things in the viewer’s perspective. His

artistic vision captures the light inherent in the things. An impression is a complex

feeling created by a thing of beauty that is unique to the individual experience

and subjective interpretation.

The association between

impressionism and surrealism is that both are initiated from subjectivity and go

beyond the edge of rationality. These two approaches mingling in the poem Banalata Sen give it extra zest. The poet

has reached a land of trance and obsessed himself in the grey domain of lost Indian

civilization where Banalata turns to intangible and idyllic like history and lifeless

like ancient sculpture. She is such a woman whom we cannot find in Natore or cannot

have physically; she is such a woman with whom the poet can sit face to face in

the darkness. She is a picture, not a physical being to be touched. Being exhausted

by tiresome frequentation of reality, he escapes into an ideal land where he constitutes

his dream.

Though the modern

poet shows interest in employing urban element in their poetry, Jibananda forms

a close relation between his poetic sensibility and nature which is sensuous, ordinary

and surrealistic. Buddadev Bashu called him nature

worshipper who unlike Tagore does not have a quest for Jiban debota. Rather

he searches for new sensibility comprising fragmentation, sensuous affluence and

incoherent sequence as we find in the last stanza of the poem. Being tired of life

and having a yearning for sleep, Jibanananda Das is certain that peace can be found

nowhere and that it is useless to move to a distant land. The tone of the last stanza

is characterized by hallucinatory fragmentation. Comparison between “hush of dew

and the approaching evening marks the overpowering silence. He employs the very

ordinary image of a hawk and gives surrealistic flavour with the weird image of

scent of sunlight. The surreal atmosphere

is created with the sense of fragmentation: when

earth’s colours fade and some pale design is sketched,/ then glimmering fireflies

paint in the story. (Das 2014)

The surrealist believes

that the notions of the outside world are overcome by invoking the powers of mind

to emancipate and escape into the world of amazing possibilities. Jibanananda Das

forges a new poetic speech to fulfil his endeavours to shape a world of his own.

He was an inward-looking person and to escape the vagaries of the mundane reality,

he formes an ideal world where his long-cherished Banalata Sen being emblematic

of Bangal’s nature is the ever source of comfort and shelter. However, a sense of

inaction and melancholy pervades the end of the poem as all birds come home, all rivers, all of/ life’s task finished. All the

images are not apparently comprehensible, and the connection between the subsequent

lines is not obvious. A sense of fragmentation occurs as he breaks the logical sequence

of words and lines.

In Banalata Sen, the poet is obsessed with the

past enchantment and its abolished beauty and allurement. This preoccupation, comprising

conscious and subconscious, past and present, makes the poem surrealistic. In the

first and the second stanzas, the poet through historical and geographical descriptions

surpasses the boundary of time and space. Using synesthetic and bizarre images,

the poet suspends rational faculty and creates Banalata an abstract ideal. The surrealist

using bizarre imagery and far-fetched idea discards rationality and intelligence.

Here the experience is centred on visual imagery. In the next stanza, the visual

experience turns to the unworldly perception created by synesthetic use of an image.

Silence and darkness are prevailing, and the poet can see her well penetrating the

darkness as the senses exceeding their natural limits, attain different kinds of

experiences. However, unlike Dadaism, surrealism instead of searching for the undesirable

and destructive aspects of life, unfolds a sense of beauty, astonishment and wonder.

In the background of his poems, distance and solitude tell us of an unknown environment

away from this sky and this world in which the poet weaves fantasy. Vigorous perception

and intense appeal for beauty put forth surrealistic ambience and this way the poem

Banalata Sen turns out to be an emblem

of fantasy and sense of wonder.

REFERENCES

Alam,

F. (2004). Trans. ―Banalata Sen‖. In S. Habib (Ed.),

Banalata Sen: Shat Bochorer Path. Dhaka: Subarna Printers.

Alom,

Z. (2013, November 11). Jibanananda’s thoughts on death, surrealism and beyond.

The Daily Star. Retrieved from www.thedailystar.net/newsdetail-207451

Anwar,

A. (2009, December 18). Surrealism: From French to Bangla literature. The Daily

Star. Retrieved from www.thedailystar.net/news-detail118252

Basu,

B. (2004). Banalata Sen: Kabbo Gronther Alocona. In H. Saikot (Ed.), Banalata Sen:

Shat Bochorer Path. Dhaka: Subarna Printers.

Falguli,

A. (2010, February 3). Jibonananda Das: Poet of Autumnul Dew. The Daily Star. Retrieved

from http://archive.thedailystar.net/newDesign/cache/cachednews-details-159509.html

Habib,

S. (Ed.). (2004). Banalata Sen: Shat Bochorer Path (2nd ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh:

Subarna Printers.

Hopkins,

D. (2004). Dada and surrealism: a very short introduction. Oxford: Oxford University

Press.

Mitra,

M. (1986). Adhunik bangla kabitay europio provab. Kolkata: Dey’s Publishing.

Rahman,

M. (Ed.). (2014). Sreshtho Kabita

Somogro: Jibanananda Das (2nd ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Rabeya Book House.

Ray, A.

(2016, May 23). Understanding Jibananda’s different poetic sensibility. Parabaas.

Retrieved from www.parabaas.com/jd/articles/arunima_poeticsensibility.shtml

Tripathi,

D. (1958). Adhunik bangla kabbo porichoy. Kolkata: Dey’s Publication.

SULTANA JAHAN. Assistant Professor in the Department of English Language and Literature, International Islamic University Chittagong (IIUC). She is a Doctoral Fellow of Islamic University and working on her dissertation on “Use of Literature in TESL in A Bangladeshi Context”. She wrote her M.Phil. thesis on Comparative Literature. Her Research interests include Comparative Literature, Critical Pedagogy and Teaching Language through Literature.

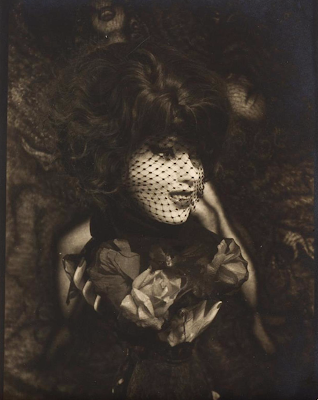

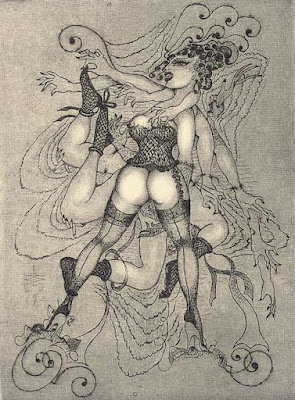

PIERRE MOLINIER (França, 1900-1976). Fue pintor, fotógrafo, diseñador y creador de objetos. En 1955, Pierre Molinier se puso en contacto con André Breton y en 1959 se exhibía en la Exposición Surrealista Internacional. En ese momento, definieron el propósito de su arte como para mi propia estimulación, indicando la dirección futura en una de sus exhibiciones en la muestra surrealista de 1965: un consolador. Entre 1965 y su suicidio en 1976, hizo una crónica de la exploración de sus deseos transexuales subconscientes en Cent Photographies Erotiques: imágenes gráficamente detalladas de dolor y placer. Molinier, con la ayuda de un interruptor de control remoto, también comenzó a crear fotografías en las que asumía los roles de dominatriz y súcubo que antes desempeñaban las mujeres de sus cuadros. En estas fotografías en blanco y negro, Molinier, ya sea solo con maniquíes de muñeca o con modelos femeninos, aparece como un travesti, transformado por su vestuario fetiche de medias de rejilla, liguero, tacones de aguja, máscara y corsé. En los montajes, un número improbable de miembros enfundados en medias se entrelazan para crear las mujeres de las pinturas de Molinier. Declaró: En la pintura, pude satisfacer mi fetichismo de piernas y pezones. Su principal interés con respecto a su sexualidad no era ni el cuerpo femenino ni el masculino. Molinier dijo que las piernas de ambos sexos lo excitan por igual, siempre que no tengan pelo y estén vestidas con medias negras. Sobre sus muñecas dijo: Si bien una muñeca puede funcionar como un sustituto de una mujer, no hay movimiento, no hay vida. Esto tiene cierto encanto si se está ante un cadáver hermoso. La muñeca puede, pero no tiene que convertirse en el sustituto de una mujer.

Agulha Revista de Cultura

Número 220 | dezembro de 2022

Artista convidado: Pierre Molinier (França, 1900-1976)

editor geral | FLORIANO MARTINS | floriano.agulha@gmail.com

editor assistente | MÁRCIO SIMÕES | mxsimoes@hotmail.com

concepção editorial, logo, design, revisão de textos & difusão | FLORIANO MARTINS

ARC Edições © 2022

∞ contatos

Rua Poeta Sidney Neto 143 Fortaleza CE 60811-480 BRASIL

https://www.instagram.com/floriano.agulha/

https://www.linkedin.com/in/floriano-martins-23b8b611b/

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário